Some time has passed since my last post, I have been quite busy travelling to conferences and meeting new people. In May I was in Toronto for Fiction meets Science (FmS), an interdisciplinary conference bringing together novelists, literary scholars, science communicators and even (some) practicing scientists. In June I returned to the Graphic Medicine conference, after missing it for the past three years, they are such a great community and a constant inspiration for me!

Being exposed to all these different perspectives and approaches to comics, writing and science communication really pushed me to think about what exactly I am trying to achieve with my comics and what do I want to study. One issue that was raised during the FmS conference, which caught me completely unprepared, was the complicated relationships between facts and fiction. The distinction may seem obvious at first but it turned out to be much more complicated when considered across disciplines, mostly because we treat facts in very different ways (as it previously emerged also during the conversation about Evidence, back in April at the Center for Science and Society).

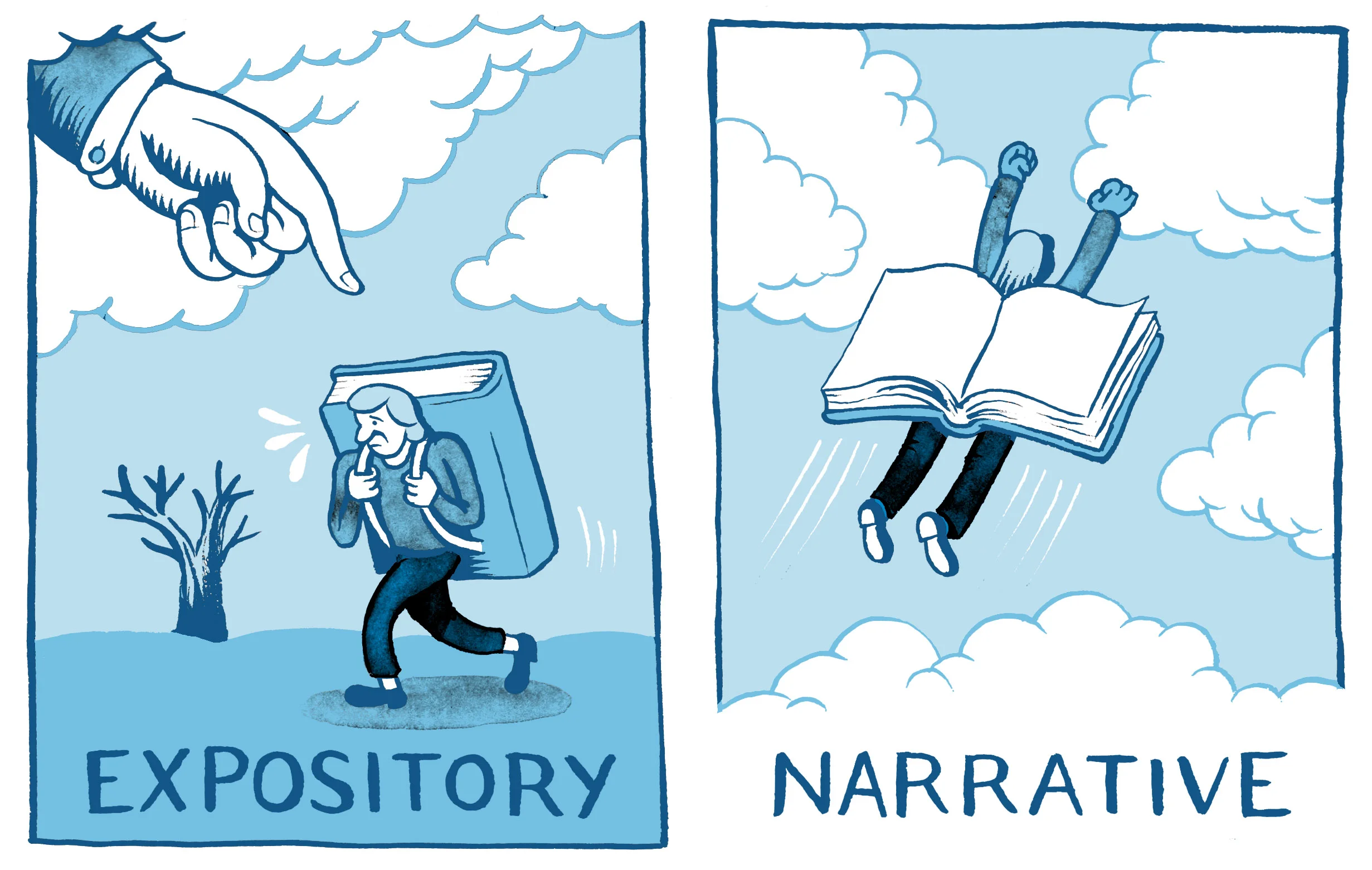

As scientists, we often like to think that we deal exclusively with facts (or data). Fabrication of data is - rightfully - considered the deadly sin of scientific research and, in general, we remain very skeptical of fiction (even if our papers often follow an obvious narrative format, the IMRaD: Introduction – Method – Results – and – Discussion - see Olson 2015). This distancing of science from storytelling is something that I often return to and I haven't completely figured out yet... it might be that the supposed 'universality' of science is incompatible with personal narratives (Ziman 2002) or that we simply underestimate the value of stories. Journalists, on the other side, are very aware of the power of narrative and explicitly embrace it in their writing, but they still go to great length to find reliable sources and fact check their information. In these disciplines there is always a clear distinction between facts (i.e. the ‘Truth’) and fiction, which is 'untrue' if not an outright lie. Novelists are supposed to be the master of fiction but - at least those I have met - are very careful to label their stories as fiction and they would never say that they are 'lying' to their readers. Their goal is not to persuade us of a theory (at least not consciously) but to present the perspective of their characters and then letting us reach our own conclusions. This is how the questionable use of fictional ‘endnotes’ and ‘charts’ in Michael Crichton’s State of Fear (presented at FmS by Joanna Radin) can be justified. However, some studies have shown that fiction may be assimilated as facts by the readers (regardless of the labels and the writer's intention - see Gerrig and Prentice 1991, Green and Brock 2000, Marsh et al. 2003) therefore the distinction between 'facts' and 'fiction' may be more important on a moral level than a cognitive one.

Then, there is science communication and creative nonfiction, where the boundaries between facts and fiction becomes even more porous and, at times, slippery. This is best exemplified by the infamous case of Jonah Lehrer (discussed at FmS by Lauren Kilian). After becoming a sort of superstar neuroscience ‘explainer’, Lehrer incurred in widespread criticism when it emerged that he had fabricated some quotes to fit his narrative. This was a particularly troubling story for me because as a science communicator I know that we are constantly simplifying or even distorting the subject matter in order to make it more accessible. The issue then is not whether something is fact or fiction but how much are we allowed to compromise factual correctness in order to meet the needs of a narrative? Should we signal this to the readers and - if so - how? Should creative non-fiction about science be avoided altogether?

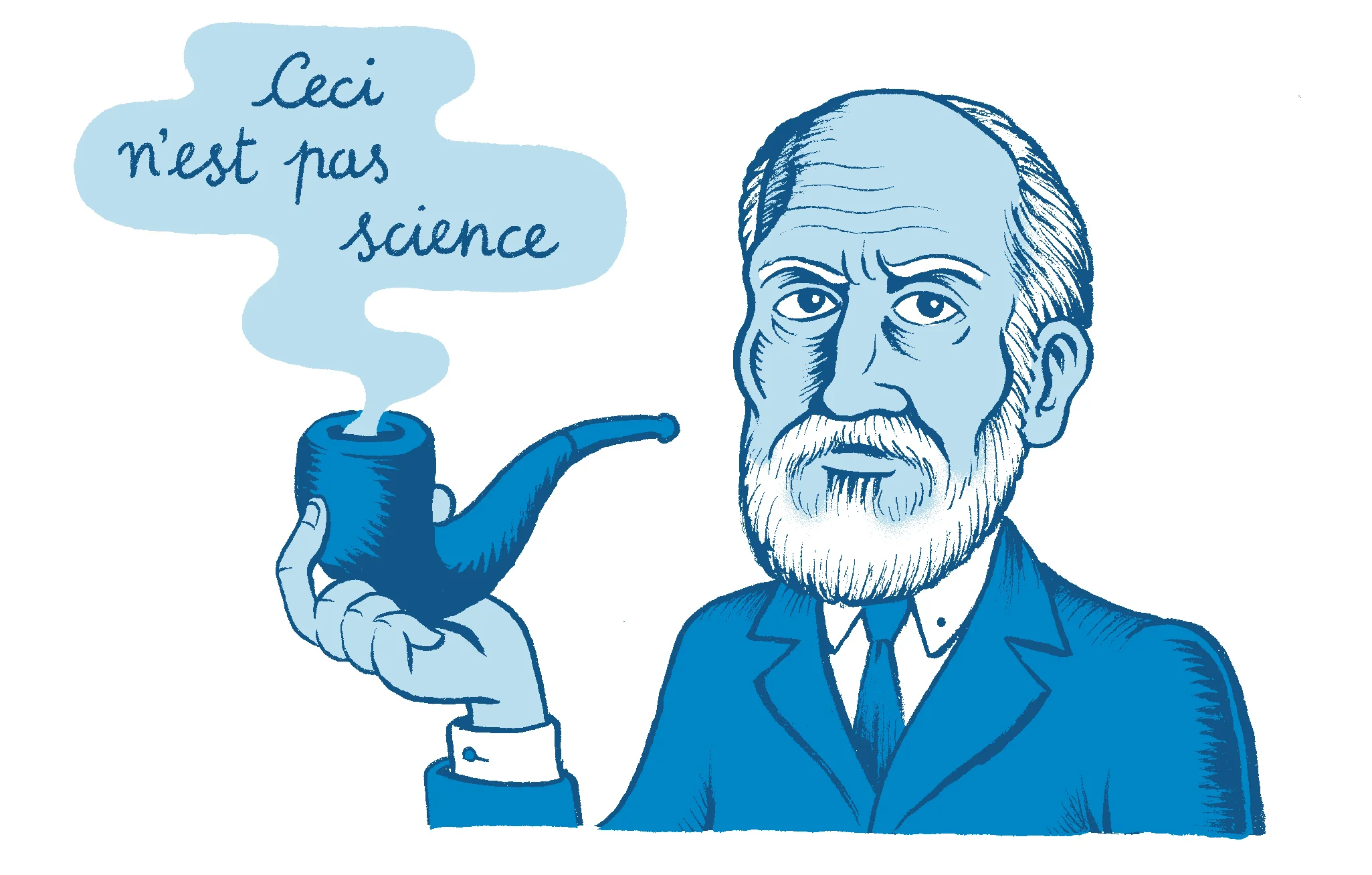

Amidst this fit of self doubt, it occurred to me that comics - once again - may provide an interesting solution to this dilemma. Because comics differ from writing in some very important ways. When reading a piece of journalism, an essay or even a piece of literary fiction, readers - even if unconsciously - seem to have very high expectations of ‘realism’. If a line or a dialogue doesn’t sound real (even if we are aware that it is fiction) the transportation into the narrative world is disrupted. Meanwhile, comics - even when labelled as non-fiction - are clearly not meant to be taken literally. As Scott McCloud (1994) pointed out (and Magritte before him) a drawing, no matter how realistic, will never be the real thing. It is meant and read as a representation, a symbol of that thing. In other words, comics ask the readers to actively participate in the illusion of fiction: believing and not believing what they are reading at the same time. In fact, the fictionality of drawing is a useful resource in science when dealing with objects outside our sensory experience. For example: an ‘atom’ will always be a model (or even a metaphor - Brown 2003) of an atom. We know that the picture is not what a real atom looks like, and yet we understand that it contains useful information about real atoms.

When it comes to writing about science then comics and other forms of visual narratives, may facilitate the blending of facts and fictions, without necessarily deceiving the reader. When reading Neurocomic (Farinella and Ros 2013), for example, I assume it is clear to the readers that the Spanish anatomist Ramon y Cajal doesn’t actually live inside the brain and never said the things he says in the comic. This is not the ‘real’ Cajal, he’s the cartoon version of Cajal, and yet the things he say are based on facts. Readers have to draw their own line between facts and fiction. In other words, by constantly exposing their fictionality comics encourage the reader to engage with the content more critically, actively evaluating each piece of information, rather than passively labelling the whole story as fact or fiction. Which, after all, it seems to me a very healthy way to read about science.

References:

Brown, T.L. (2003). Making Truth: Metaphor in Science (University of Illinois Press).

Gerrig, R.J., and Prentice, D.A. (1991). The Representation of Fictional Information. Psychol. Sci. 2, 336–340.

Green, M.C., and Brock, T.C. (2000). The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 79, 701–721.

Marsh, E.J., Meade, M.L., and Roediger III, H.L. (2003). Learning facts from fiction. J. Mem. Lang. 49, 519–536.

McCloud, S. (1994). Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (New York, NY: William Morrow Paperbacks).

Olson, R. (2015). Houston, We Have a Narrative: Why Science Needs Story (University of Chicago Press).

Ziman, J. (2002). Real Science: What it Is and What it Means (Cambridge University Press).